The story behind the book 4.5 years by David Taylor

His brother George's war story

|

| amazon book link |

| David Taylor at 90 |

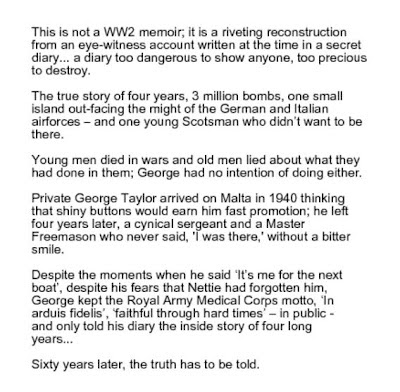

Among the pile of manuscripts waiting feedback from me was one - a very good one - about a novelist's background research into her family tree. While I was reading this, someone asked me why David Taylor's book is listed as mine, so here is the story behind the book.

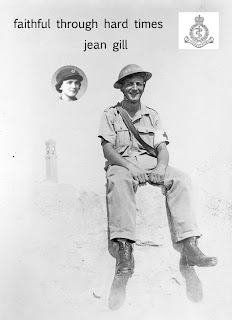

I was writing a book about the siege of Malta in WW2, using my father's 33,000-word illicit diary, written at the time, and I needed family and contextual background information to decode parts of the diary. My parents were dead and my mother hadn't shown me the diary until after my father died, so my head was full of questions I couldn't ask him. I was living in Wales at the time, and I wrote to my uncle, my father's brother, now in his 80s if he was still alive, and living in Canada. I included my email address, in case a relative wanted to reply to me.

'We'll continue like this now,' came the email reply from David Taylor, my uncle, very much alive, and there began a special friendship. At some point, he wrote, 'Aren't you interested in my war story?' and of course I was, so I found myself writing two books in parallel. At the same time as writing my father George's real-time story in 'Faithful through Hard Times', I was ghost-writing his brother's memoir of life in a Prisoner of War Camp.

Receiving Dave's email accounts of being captured in France, of his escape attempts and of camp life, was like receiving news from the Front three times a week. I was completely caught up in his story. He and George were in their early twenties and their youth came across in their both their accounts, of killing and football, starvation and pretty girls. All the surreal paradoxes of wartime hit me fresh; Dave clearly re-lived this period as the most intense of his life and yet he referred to it as '4.5 years' because he felt he had lost 4.5 years from his life. That's why I chose '4.5 years' as the title.

Dave didn't know I was writing up his memoirs as a book. It was important to him to tell his story and he became more and more competent with the keyboard as he continued, typing his fingers sore with longer and longer emails. I typed it up first as a booklet, for his approval, and for his family to have copies. I thought I could use the material for a novel and Dave gave me copyright as a gift - a very precious gift. However, the more I thought about it, the more I felt the book was a precious witness, like his brother's diary, not to be fictionalised.

| Dave and his wife Gladys, after 62 years of marriage |

My husband and I managed to get out to Toronto on holiday to see Dave, just before he was 90, and by a miracle of timing the copy of '4.5 years' that I'd published as a surprise for him arrived in the post the last day we were there. He was almost pleased to get rid of us so he could read his book. His wife, who'd married him when he returned home to Scotland, looked at the cover and said how handsome he looked. That made his day as much as the book itself.

Some memoirs are 'merely' personal; they don't reach outside the family. Others touch strangers. From the reviews and sales, it seems to me that Dave's story reaches out beyond 4.5 years of one man's life. It had a great review in the journal of 'The Association of Scottish History Teachers' and passed the test of readings by military historians. Yet it remains personal, with the voice of an enterprising young Scot who played the accordion, spoke fluent French and who was dangerously charming to women, whatever his age.

At 90, he figured out how to use skype. 'We'll continue like this now,' he told me, and so we did. Daily conversations in which we figured out how a medieval watermill would have worked (for my novel's research) or worked out some dubious parentage in our family tree. I told him an online questionnaire had me living till 82 and he said 'You can do better than that!' There was an honesty between us that made it easy to speak of death but neither of us really thought he would be caught so young, at nearly 92. Sometimes I hear him in my imagination. 'We'll continue like this now,' he says.

He had the chance to enjoy his book and to lend it to those around him. When the fire brigade called because of his wife's emergency fall, they went away with a copy of '4.5 years'. He would be so pleased to hear how many people have bought his book but there would always be one statistic that counted most for him. 'Is my book doing better than George's?' They are in fact neck-and-neck on sales so the brothers' rivalry continues. And I will never choose between them - they're very different.

| Dave Taylor at 90 |